How to Use a Compass - Lesson Three

Magnetic and Grid Declination

Vitally Important: Declination only applies when you are using your compass in conjunction with a map!

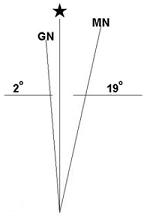

You know that the red end of the compass needle always points north. What you didn't know, until now, is that there is more than one north. The compass is pointing at magnetic north, shown as MN in the image to the left. This is the point on the globe at which all compasses point. The exact spot moves from year to year as the earth's magnetic field fluxes and changes.

The second north is geographic north, which is also called true north. That's the star (*) in the diagram. This is the exact physical spot we know as the North Pole. I'm sure you can imagine the candy-cane striped pole stuck in the snow. I will use the term true north in the remainder of the lessons.

The third north came into existence with the advent of GPS satellites and receivers. That third north is grid north, or UTM grid north. This is GN in the diagram. Some maps have both meridian lines, which point toward true north (*) and a UTM grid which references grid north (GN).

The three norths are physically located in three different places on the globe. The difference in the direction of each of those places from where you are standing is called declination.

For example, let's say you are standing at Point A. The compass needle on your compass is pointing toward magnetic north (MN). If you could draw the meridian lines on the ground, they would be pointing toward true north (*). You would then be able to see that the direction the compass needle is pointing doesn't exactly line up with the meridian line. The UTM grid line, if drawn on the ground, would also be slightly off from both the meridian line and the direction the compass needle is pointing. Again, that difference in direction is called declination, which is measured in degrees.

Declination can seriously affect the direction in which you should be hiking, so you need to correct for it. First, you need to know what the declination is, in degrees. This depends on where on the earth you are. You may have to find out before you leave Lesson One, but your map may have some declination information already printed on it.

One thing you have to know is that magnetic north moves! Magnetic declination can change significantly with time. If you have magnetic declination information from three years ago, it's out-of-date. You need to know what the magnetic declination is this year.

Grid north doesn't move, so grid declination doesn't need to be recalculated.

If you know the longitude and latitude for a specific location in either decimal degrees or degrees, minutes, and seconds, you can find out the magnetic declination for that location at the National Geophysical Data Center. You can also find the current magnetic declination by going to Magnetic Declination and clicking on the map.

When you are plotting out a course, you will do that just as described in Lesson Two. Be sure you know whether you are lining up the compass's orientation arrow on the meridian lines or the grid lines. It makes a big difference and can mean the difference between arriving at your destination or being lost.

Accounting for Declination

Now that you know about declination, you can take that into account, too. To do that, you must add or subtract a number of degrees from your desired bearing. You will either add or subtract the number of degrees between MN and * or MN and GN, depending on which lines you used to plot your course.

The magnetic declination in the diagram above is given as 19° and the number is to the right, or east, of true north. The grid declination is 2° and the number is to the left, or west, of true north. Numbers to the right, or east, of true north (*) are positive and numbers to the left, or west, of true north are negative. True north is zero.

Your objective, when dealing with declination, is to get back to zero or true north. Since your compass is pointing at magnetic north, and since magnetic north is 19° greater than zero, you need to subtract 19° from your compass reading to make sure you are truly going to be hiking in whatever direction you wish to go.

You can make the adjustment by rotating the adjustment bezel on the compass housing to subtract some number of degrees from your desired bearing. If you used the grid lines to determine your bearing, you'd need to subtract a total of 21° from the bearing on your compass. Why twenty-one degrees? You need to get from MN to GN, and that's a total of twenty-one degrees on this map.

How about an example?

Let's assume you've used the map and compass and have plotted out a course. The initial direction, or bearing, you need to hike, according to the compass, is 225°. That happens to be Southwest. If you were to ignore the declination of 19°, you would actually be hiking on a bearing of 244°. That's nineteen degrees more than 225°. To make the correct adjustment, you would turn the adjustment bezel to subtract 19° from the original 225°, so it would appear that you will be hiking on a bearing of 206°. That bearing will get you to where you want to go.

Determining Magnetic Declination

You may not need to determine the declination before you leave home. There is a fast and pretty good method to find the magnetic declination while you're in the field. This method also has the advantage in that it corrects for local conditions that may be present. Of course, it also presupposes that you know where you are and can locate at least one known point in the distance. Here's the process:

- Determine, by map inspection and compass use on the map, the apparent bearing from your location to a known, visible, distant point. The further away that point, the more accurate the declination will be. Pretend you can't see the actual distant point while you're using the map and compass. Note the bearing you find.

- Put the map down and sight on that distant point with the compass and note the magnetic bearing. You do that by turning the adjustment bezel on the compass housing so that the orientation arrow is aligned with the compass needle. Read the number from the adjustment bezel where it meets the base of the direction of travel arrow.

- Compare the two bearings. The difference between the two bearings is the magnetic declination.

- Update as necessary. You shouldn't need to do this very often, unless you travel in a terrain with lots of mineral deposits.

Uncertainty Factor

You can't always expect to hit exactly what you are looking for. In fact, you must expect to get a little off course.

How much you get off course depends very often on the things around you. The density of the forest, the ruggedness of the terrain, and the number and difficulty of the obstacles in your way will all affect your ability to get from Point A to Point B. They will all cause you to veer off course. Naturally, much depends on how accurate you are, too. You do make things better by being careful when you plot a course, and it is important to aim as far ahead as you can see.

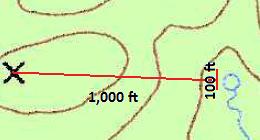

In normal conditions, the rule of thumb is that the uncertainty factor can be as much as one tenth of the distance traveled on each leg of your journey. If you use this figure as an example, you would travel a total of 1,000 feet from the hilltop on the left to the spring on the right. It is possible that you might end up a little off course, perhaps by as much as 100 feet. If you're looking for something smaller than 100 feet across, there is a good chance you'll miss it! That spring is certainly not 100 feet across!

Now it is time to get into the backyard or a nearby park for some practice, and then the backcountry once you're familiar and comfortable with using a compass.

Good luck!